| WRITINGS |  |

||

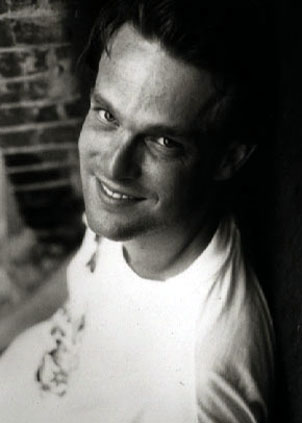

Nevermind The Myth, Here's Kurt Cobain September, 2001 I knew Kurt Cobain. Not as well as his bandmates, family, and dysfunctional wife, but as well as any casual observer who caught a glimpse of his brief flickering flame, before Cobain tragically offed himself in his Seattle home. As journalist Charles Cross notes in his August release, "Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain" (Hyperion), "after the [September, 1992 Seattle Center Coliseum] show, Kurt blew off all interview requests except one: Monk. When Monk's Jim Crotty and Michael Lane made their way to his dressing room, they found it deserted except for Kurt and [3-week-old child] Frances. 'There was all this activity outside,' Crotty remembered, 'and then you open the door, and there's Kurt Cobain holding a child in an empty room. He seemed so sensitive, exposed, vulnerable, and tender....'" Cross goes on to write that my conversation with Cobain was "the greatest myth-making session of Kurt's life. When asked about Aberdeen, [Kurt] told a story of being run out town: 'They chased me up to the Caste of Aberdeen with torches, just like the Frankenstein monster. And I got away in a hot-air balloon'...." Looking back, while caught up in the excitement of rainy Seattle's brief moment in the sun, and the wry melodic brilliance of Nirvana's major label debut, Nevermind , the band's performance that night at the Seattle Center Coliseum was a letdown. Cobain's bandmates, Dave Grohl (Foo Fighters) and Krist Novoselic, always felt, and I had to agree, that Nirvana, like most indie bands, came across better in a small club. Up on that large Seattle Center stage, the band seemed formulaic, distant and small. The anarchic energy of genuine punk was lost, even though the Seattle kids still moshed with characteristic abandon. The real show that night was backstage, amidst Northwest rock royalty, watching Love--the brassy, bossy, grossly pimpled, chain-smoking, agonizingly needy, if, at times, brilliantly catty, prima donna--prance around the green room in huge black high heels, trailed by a tandem of low-life sycophants clinging on her every outburst, as she lambasted "Lynn Hirschberg," the Vanity Fair writer who wrote a scathingly honest report on Love and Cobain's notorious drug habits. Lost on Love was the irony in her intermittent pestering of the besieged Novoselic for some psilocybin "shrooms." Though it might seem like a cheap shot now, I never thought Cobain qualified for "genius" status--by his own and bandmates' admission he was a "sloppy" guitarist, and allegedly knew only a few chords. Yet I couldn't deny his inimitable charisma either. Though one is hard pressed to separate the glow that surrounds genuine artists from the projections that come with fame, Cobain exuded unmistakable star quality. Nevertheless, as Cross explores in his searching, precise, if, at times, overly earnest biography of the ill-fated "rock" legend (no true observer of the so-called "Seattle Scene" ever used the pretentious and pointless term "grunge," except with tongue-firmly-in-cheek), Cobain was no enlightened bodhisattva crucified on an altar of the media leviathan. Cross makes perfectly clear that Cobain consciously sought fame ("I'm going to be a superstar musician, kill myself, and go out in a flame of glory," the 14-year-old Cobain wrote in his journal). That Cobain enjoyed wielding the power that came with fame is also made obvious, even as Cobain wore the charming DIY mask of self/rock/celebrity abnegation. As Cross points out, Cobain was the first rock "anti-celebrity," but a celebrity nonetheless. And despite what Kurt's otherwise abhorrent wife adroitly dubbed his lame and cowardly, and I might add, disingenuous death note--regretting he could not live up to the rock idol he helped create--Cobain courted as much as he abjured what Joni Mitchell called "the star-making machinery behind the popular song." In fact, of his own free will, Kurt wrote almost nothing but catchy pop tunes, modeled after, and at times nearly plagiarized from, those masters of catchy pop, the Beatles. And when push came to shove, and Geffen Records threatened to pull the release of an unsuitably "raw" and uncommercial "In Utero," Cobain willingly caved in to the label's request for a remix. Being "difficult" and "indie" was another arbitrary pose for an artist who didn't define himself by his "rage against the machine." That all of this is true of Cobain is what makes him slightly more fascinating than your standard rock casualty, from Jim Morrison to the overly praised Janis Joplin, whose post-mortem stature grows more because of outsized myth, born of their biographers' own needs, than unadorned greatness. What also makes and made Cobain special is that he achieved canonical status with so little creative output. Like the legendary James Dean, who crashed and burned after only three major films, Cobain made only three albums of original music--the rest were outtakes, B-sides, throwaways, or unplugged versions of the standard Nirvana repertoire. The true biography of Cobain as musician has never been about what he accomplished, which was the equivalent of his beloved Beatles quitting after "Revolver," but of what he could have become had he not toyed with real and metaphorical revolvers. But, of course, as with so many rock legends, there was a far bigger love in his life--way beyond family, wife, and music--which allowed him to handle almost everything else with near selfless aplomb. I experienced this phenomenon first-hand. As Cross notes, "the second week of November [1992] Kurt did a photo session for Monk--he was to be on the cover of their Seattle issue. He arrived alone at Charlie Hoselton's studio, and unlike most photo sessions, cooperated fully. 'Here's the deal,' Kurt told Hoselton. 'I'll stay as long as you want, I'll do whatever you want, you just have to do two things for me: Turn off your phone, and don't answer the door if anyone knocks.' Monk editors convinced Kurt to dress like a logger and pose with a chainsaw. At one point during the shoot, Kurt dared to venture outside, and when Hoselton asked him to pose in front of the espresso machine, Kurt did one better--he pushed the barista aside and made a coffee." After the fabled, darkly prophetic cover shoot, which featured Cobain, myself, and my fellow "Monk," Michael Lane, dangling from a cracked space "needle," Cobain asked Michael if he could catch a ride "home." Michael ended up driving Kurt to a series of stops all over downtown Seattle. At each of the stops, Kurt would disappear for a few minutes, and then pop back to the car. After the final stop, Michael noticed something different: a smile, a relaxation, a sense of peace. Cobain, the serene savior of rock 'n roll? Cobain, the enlightened warrior, staring into the heart of darkness, while teaching us how to transcend the gluttonous fame machine? Cobain, the sensitive working class kid, who channeled lyrics of a haiku-like power mixed with guttural spasms of emotional depth? Or, Kurt Cobain, just another Seattle junkie? With the skinny kid from Aberdeen, it was always "all of the above"... and more. |

|||

| HOME WRITINGS RESUME PRESS CONTACT BACK TO TOP | |||