| WRITINGS |  |

||

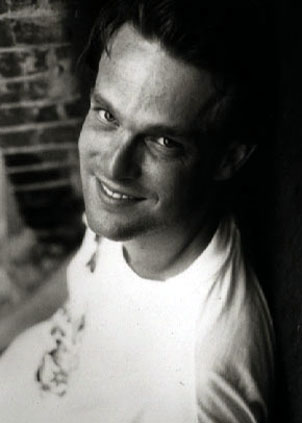

HIGH STYLE, SPECIALIZATION, YOU CAN GET THE GIRL: Assistant Secretary of State James Rubin Shares the Secret of His Success. March, 1999 Meet James Rubin: State Department Spokesperson, arms control expert, aide and confidante to Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, husband of CNN foreign affairs correspondent, Christiane Amanpour. Shortly after a morning press briefing, we catch Mr. Rubin in his neat warm office, which, like Rubin, is in striking contrast to the State Department's sterile exterior, and its hospital-like corridors. Handsome, tall, smart, with a glint in his eyes and a playful smile on his lips, Jamie Rubin is in command here, excited to be the subject of our profile, generous with the details of his life, but cognizant of the ways and needs of the press. It's his job to stay abreast of those ways and needs, and to be helpful while ever mindful of the policy directives of his boss and his "boss's boss," the President of the United States. His allegiance to two masters, his own love of the spotlight, his assured command of his personal image all persuasively come together in that suave, poised, incredibly ERECT Rubin swagger, which says, in so many words, "There's war in the Balkans, troubles in Iraq, but, gentlemen, isn't it a fine thing to be alive, filled with purpose and the vigor of youth, the promise of the future, damn fine thing indeed." Rubin's demeanor says gusto, confidence, peacock pride. A master of his universe, doing noble work in style. The peripatetic wife was home last night. "Indeed, gentlemen, indeed. Life could not be better." We half expect Mr. Rubin to whip out a fine Cuban cigar and a glass a sherry and toast us one and all. But these are different times. Abstemious times. And while Jamie Rubin's enthusiasm bubbles over, he must be ever mindful of public reaction. Like many in Washington, he stakes out his rebellion in small gestures--a snazzy tie, a pack of smokes. The latter gesture lends a hoarse gravity to his beautiful boyish facade. When Jamie gives his daily press briefings you can sense his physical discomfort, as if the nicotine is choking away the youth. By design. Without that habit, the voice would be too high, the dismissive air wouldn't play. Rubin would be another Stephanopoulos--a young, bright, Clinton "kid," with a Columbia degree, and a sweet smile, eaten by the Washington wolves. But James Rubin will not go into that dark night. Though he has stumbled, he is determined not to fall. He's a player, not a victim. We like Mr. Rubin--a kind of Jewish John-John, with the same bourgeois conceits, but smarter, wilier, with less of a pedigree, but more of a purpose. And so we begin, periodically interrupted by calls from wife Christiane, the subtext of our interview. They met in the Balkans. No Casablanca as far as war-time romantic backdrops go, but it's what was available in the late 1990's. And, as this article goes to press, it is what is dominating the international news. MONK: People have said you were the most wanted eligible bachelor in D.C., and then you got the girl. How did that happen? JAMIE RUBIN: It's hard to know what the features are that attract the opposite sex. I know I am attracted to women who do interesting things, who don't want to just sit around the house, who are good looking, who are funny and who share a sense of humor. Clearly, being very visible through the State Department, being on television, being known, creates a certain appeal in our culture. Being known is almost as important as being rich. Now, I don't have any money, so in the old days someone who could attract women if they were rich has been translated to the attraction of being known. So to that extent, I gained attractiveness by being known. I make a government salary. I was single. I didn't have much time for a personal life, so I spent my money, to the extent that we make money in government, on clothes and restaurants. That's it. I have very little furniture. When my wife came and saw my apartment, she threw out everything and declared it post-college issue Ikea. It all went. So I spent money on clothes. In Washington it is not common for men, or women for that matter, to be very focused on their clothes. And I, because of my job, wore nice clothes. So people wrote that I was well-dressed. You put all that together and I guess I became known as an eligible bachelor. Plus, I do think that women are attracted to people who have interesting jobs. If you're in an interesting job and if you're doing something that matters to you and is important and isn't based on some crass, commercialistic value, I think that's attractive. Now, I was attracted to the same kind of person, who was in an exciting field; had shown her toughness on issues that I cared about. I think we developed an intellectual, emotional bond over the subject of Bosnia. Because when I worked for the then-Ambassador to the U.N., I was very passionate about American involvement to resolve the siege of Sarajevo and the war in Bosnia and that was what she was telling the world about. So even before we knew each other, we had a bond. M: Can you replay that moment when you and Christiane met over the skies of Bosnia? How did that happen? JR: Well, she was in the back of the plane covering the Secretary of State's trip to Yugoslavia. We went to Belgrade, capital of Serbia; Zagreb, capital of Croatia; and two cities--Sarajevo and Banja Luka--in Bosnia. So in the back of the plane there are the journalists who cover the Secretary. I think the Secretary was coming back to greet the journalists, and I was with her. There was a moment when somebody spilled their popcorn and I went down to fill it up and we looked at each other. Then later that night I asked her to go out for a drink. It was very late, 2:00 a.m. in the morning. I had taken my suit off and put on a black leather jacket and jeans. She cracked some joke like, 'aha, government official relaxing.' And then we drank some margaritas and we made a point of taking each others' phone numbers. Then I asked her out for dinner in New York City and that was the beginning of the best thing that ever happened to me. M: Are there any Clintonesque signals that you do while Christiane's in the briefing room and you're up there on the podium to indicate "I'm thinking of you, honey"? JR: Well, it's not that simple. The question of her covering the State Department was raised as an awkwardness that we needed to deal with. But the fact is we don't have to deal with it because she doesn't cover the State Department. When she's in Washington, she's not working. What her job is, is to go out in the field and cover Iraq or Kosovo or Tehran. She goes out and does a story about what's going on in that country. She doesn't cover what it is the U.S. Government is doing every day. So there really isn't that kind of interaction. M: Is there a clear separation of church and state? JR: First of all, on that issue, there are hundreds of men and women who are married in this world of journalism and government. The only reason that [Christiane] and I became a subject of conversation is because we're more prominent. There are people who work in Congress who are married to reporters who cover them. What I believe is our bosses have to trust us. They have to trust us to have the integrity to do our jobs. Her bosses trust her to cover the news without fear of favor, and my bosses trust me to present the Administration position as compellingly as I can. So just as a defense lawyer and a prosecutor are married in cities all over the country, and during the day they have to make different arguments and present different cases and do different things on the same subject, we do it on the same subject. There are hundreds of marriages where it's much more complex, where the government official is not trained to be wary and to know what signals you can send to give journalists confirmation of things, to know how far you can talk on the record and on background. If there were a person in the U.S. Government who was best trained to spend time with journalists and, therefore, married to a journalist, I would argue it's me. If there was ever somebody who was least likely to be affected by working with, living and married to a government official, I would put her on that end of the spectrum. She's established her independence over a long, long period of time, whether it's in Bosnia or Iraq or in any part of the world. I think her bosses believe that her integrity is unquestionable. I hope mine do, too; I think they do. She serves Ted Turner and the head of CNN. I serve the President and the Secretary of State. I believe the President and the Secretary of State have charged me with this because they think I'm good at it. I do not believe that they think I would compromise my work for them to do something for my wife. M: One of the things we try to do as Monks is get at the spirit of a place from a lot of different angles. If you had to list your private Washington, D.C., not the standard tourist stuff, but stuff nobody knows about, what would you list? JR: I'll tell you what, we can go upstairs and you can take a picture of where I smoke my cigarettes--since I'm not allowed to smoke in the building--which is on the balcony of the 8th floor of the State Department. M: There's a hidden place. JR: They're not hidden, but one of the things that I do in spring, summer and fall is get on roller blades and roller blade through Rock Creek Parkway and end up on this particular bench with all my newspapers and my cell phone, and spend my day working on the weekend there instead of sitting in the office. There is a restaurant called Cashione's. It's down the street from where I live and the bartenders know me there. I can come in and just sit at the bar with a magazine and read while I'm eating and nobody bothers me. That's an example of that. And there's a small group of me and my friends, we kind of get together for dinner whenever we're all in Washington. We have what we call "no fault dinners," which means we can say anything we want and it doesn't leave the table. We can yell and scream about each other and talk about our bosses in ways you can't. I think it partially works because we're all in the government; but when I walk around Washington, I don't have any freedom to sit at a bar and say what I think. People know me and will quote me and use it against me. So we used to go to this empty Korean restaurant. It was on 24th Street across from the Hyatt over there. It closed about six months ago. So we've been finding other places, but it's never been quite the same. M: Now, I hate to cast aspersions on D.C. style, but obviously you're a person with a greater sense of style than the average person working in government. If you had to describe the elements of D.C. style, what would they be? JR: I can't do that on the record. It would be helpful. I'll try. M: Oh, come on, that's what they need. If you had to be an image consultant to the average government employee-- JR: Look, I think working in Washington government is not a well-paid profession. The public has been ginned up by a variety of political means to not want its government officials to live well or have any of the creature comforts of people at their stage in life and capability who have it in the private sector. If you go to Europe, a government official who's an assistant secretary of state or something like that, the European public expect that person to fly first class, to eat at fine restaurants, to have a car and a driver. Now, being a different kind of society, in America that's not okay. So guys in top level positions don't get all those perks of office. So clothes are a symbol of that phenomenon. If you're a government official and you're dressing too nicely and having too much style, then wait a minute, you must not be understanding that you're a representative of the people. Now, I don't believe that. I don't believe that most Americans begrudge me for spending my government salary on nice clothes or a nice car, if I explain to them that I don't have a family and if I were in the private sector I'd be making ten times as much money as I am in the public sector. So with my $100,000 is it okay if I have a few nice ties? I don't think they would have a problem with that. But if it's presented in a very truncated way--top government official spends thousands of dollars on suits--they don't like it. That's our money he's spending. It's all a question of how something's presented. So that phenomenon is what generates a lack of style or concern about spending money on frivolous things or what are perceived to be frivolous things like clothes. So I probably have pushed the envelope a little bit, and I'm comfortable with that. At some level I need my releases because I do work so hard. M: This cognitive dissonance of we are private people, on the one hand, yet we also work for the government, causes some of the problems that happen in this town when you try to have a private life, yes? JR: Well, obviously, you've got your finger on a very, very sensitive question right now. You're asking me about my private life. Okay, I'm a public figure. So you've chosen to insert yourself and the public into my private life. Now, I'm the spokesman and I can't deny some discussion of myself because I am every day the face of the U.S. Government when the Secretary isn't speaking abroad to the rest of the world. But journalism is partially responsible for the breaking down of the private lives of government officials. Journalists have made the private lives of government officials part of their investigative powers. The investigative powers of journalism and government have increased. I think you've asked a legitimate question, but it's a very complex question that involves our society and how Washingtonians feel about their private lives. It involves the extent to which journalists have decided that if he's my elected President, then he should be subjected to scrutiny. And how low does that go? M: I think we've seen that. Did we go too far with Clinton? JR: I cannot comment on that as Assistant Secretary of State. M: Back to romance. Who are the five uber "babes" of Washington, D.C.? Pick the ultimate women you just think are hot, smart, that meet the criteria you established at the beginning of this interview of what, in your mind, classifies as a great gal. JR: I think if I answered that question it would interfere with the smooth functioning of my marriage. M: You're married, though. Isn't it fair game to just say, these gals are great, but I didn't choose them? JR: I just don't see what I would get out of answering that question other than a heap of trouble. M: Well, all right, put it this way. There's 2 million Monk readers around the world that want to know, if they come to D.C. , what advice would Jamie Rubin give them on how you get the girl? JR: I think how you get anything in Washington is the same advice. The more you climb the Washington ladder, the more you become appealing to women. That's just a fact, just like it is in any city. M: Well, that's not always true, but in this city it seems to be that power is the aphrodisiac. JR: Well, no, because the ladder is defined differently in other cities. In Los Angeles or New York, there are 20 different ladders. There's the musician ladder; there's the artistic ladder; there's the business ladder; there's the banking ladder. In Washington, it's just that it's one ladder; it's called government. My best advice is to develop some issue that you're very good at, that you're interested enough in to work really hard at, and then learn not only the substance of that issue but the politics of that issue, the journalism of that issue, the history of that issue and the future of it. You will quickly find yourself special. If you're good at one of those issues, you will find yourself being invited to the right places, being talked to by the right journalists, being talked to by the members of Congress and the government. And you will find yourself in a very interesting social environment from which it's up to you to strike out and find what you're looking for. M: So specialization in Washington is the ticket to getting into the bigger pool. JR: Right, because once you're a specialist then other specialists talk to you. They also think you might be knowledgeable about things you don't know anything about because you're a specialist. So the advice I give interns, I give graduate students, is that's the best way to climb the ladder. And I believe that the more interesting you are professionally in Washington, the more there is an attractiveness about you. M: So you want to pick a sexy specialization? Bosnia's not sexy. JR: Well, you'd be surprised. That's how I found my wife. |

|||

| HOME WRITINGS RESUME PRESS CONTACT BACK TO TOP | |||